The TGCI Liberian Citizen-Government Engagement Project (CGEP) seeks to engage citizens and government in interventions to combat child sexual abuse and gender-based violence in Liberia. It works in areas of the country where there have been widespread reports of child and youth sexual abuse.

Through engaging citizens with publicity and an SMS and hotline system, the project addresses sexual abuse and rape by increasing knowledge of the issue, rates of reporting, response by government offices, and persecution of perpetrators. It is currently scaling up coverage from two counties to four.

Learning from implementation

Unlike many projects that only conduct baseline, midterm and summative evaluations, CGEP uses a ‘feedback loop’ learning approach to its activities. This means regularly engaging citizens, government officials and project staff in feedback loop data-gathering through collaborative reviews of the project activities and outcomes, which draw on findings from field research into the impact of the project.

These ongoing cycles of conversation are an opportunity to analyse, understand and improve current practice, and to guide future activities - allowing for a dynamic evolution of the project as it is implemented. This blog shares what was learned about the implementation of the SMS and hotline system during one feedback loop cycle from early 2017, and reflects on next steps.

The research process involved diverse project stakeholders in 14 focus groups and 26 key informant interviews across four counties. Young people, teachers, police officers, social workers, government officials and judiciary members discussed their perceptions of and experiences with the SMS and hotline system; interview questions focused on responses to incidents of sexual abuse report through the system. The findings are grouped into four key areas.

Citizen awareness and knowledge of project SMS / hotline systems

- The main reasons for using the project hotline were the confidentiality offered to those reporting sexual assault, increased likelihood of a response, reduced potential for perpetrators to escape and to deter future crimes.

- The idea of using an SMS or hotline system was familiar to many because a similar hotline had been used during the Ebola outbreak.

- In some communities, there were multiple hotlines (for example, for the police or hospitals) and this was confusing for some.

Citizen awareness / knowledge of sexual abuse awareness raising and behaviour change messages

- Schools were a key space for awareness raising and behavior change, and lessons learned by students were shared with families and friends. In some schools, organisations emerged, such as buddy clubs that discussed prevention strategies for rape and child marriage.

- However, schools can also be unsafe spaces, with predatory teachers or administrators. One child and women protection officer talked about how schools have had to explicitly implement ‘no sex for grade and no grade for sex’ policies. Children were given information about where to report cases if teachers or administrators demanded sex from them.

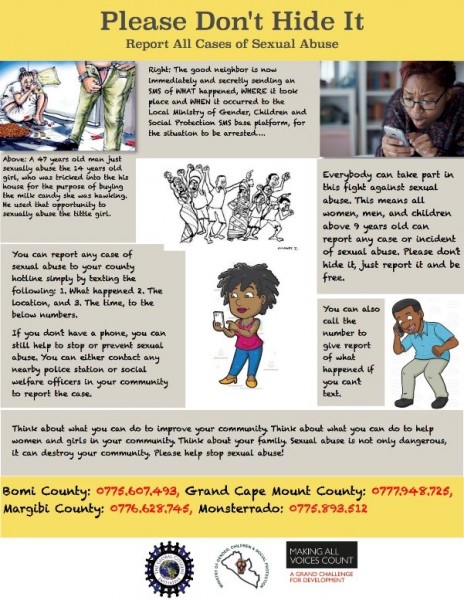

- Other interventions took the form of community meetings, radio jingles, fliers and posters. The main messages of these interventions included concrete information about the SMS / hotline system, ways to prevent sexual abuse, and the consequences for perpetrators.

Incidence of reported and registered sexual abuse through SMS and/or telephone hotline

- In many communities, low literacy levels impaired the utility of the hotline. A community leader noted that “Anything that involves writing and reading makes people shy away and think that only those who are educated can be part of such thing.”

- Limited mobile coverage, uneven access to and technological challenges with phones meant the SMS / telephone system was not always available at times when victims most needed it. An important area for future research is to examine how distance and rurality impact the reporting process.

- There were mixed perceptions of the system’s confidentiality, and there were fears that reporting could be hazardous. There were also many instances in which the perpetrator was related to the victim or to the potential reporter of the crime. Several participants expressed a desire for some support - such as a safe location, or money - for those who came forward.

Response and referral of reports of child sexual abuse

- Rurality limited police ability to get to crime scenes and respond to cases; in some cases, evidence was destroyed and perpetrators escaped. Lack of transport was pervasive to all aspects of the response process and prevented victims from getting prompt medical care, officials from reaching crime scenes, and all parties from accessing court facilities during the trial phase.

- There was a sense that at any point these cases could be ‘compromised’. The word compromised was used by participants to refer to cases where deals were made or complaints were dropped rather than reaching adjudication. The pressure to not pursue cases was widespread. One focus group shared that “community people’s view of rape is different, therefore they do everything possible traditionally to compromise the case. They don’t see it has a crime but an opportunity to marry girls under age.” Community officials could be complacent in the compromising of cases by demanding bribes, refusing to act, or destroying evidence.

Adjusting our practice and next steps

As a result of the stakeholder group recommendations, the TGCI team intensified its awareness campaign approach, and strengthened its targeting of women and children. For example, more of the awareness messages on radio stations were directed towards the women and children who the consultative groups suggested lacked confidence in sending reports of sexual abuse to the system. The team printed smaller pocket versions of our awareness posters and targeted these towards market places, churches, mosques - as well as at gatherings of youth and women’s organisations.

A third feedback loop cycle began in May 2017. This field work will inform consultations with citizen, government officials and project staff consultations in each county, seeking to use that information to improve strategies, messages, access to the hotline and SMS system, and the presentation of results from the government database systems.