Local priorities get overwritten (yet again, yet again, yet again)

A deafening 30-second silence filled the room.

It came after over two hours of animated discussion between representatives of organisations using technology in transparency for accountability projects, gathered together in the Philippines’ capital city, Manila.

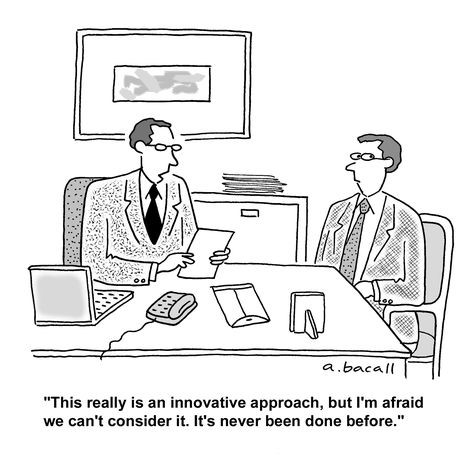

The elephant in the room was that many of the organisations were prioritising technology in their funding applications. This was not because they felt it was their greatest need - but because Northern donors were pushing for new and exciting technologies. So we asked “In an imaginary world where you were free to determine your own priorities would technology be what you were emphasising in your funding proposals right now?”. Silence was the awkward response.

When eventually the silence broke the first person said that their real preference would be to invest more funds in their existing practices that were already delivering the best results. The problem was that funding for such work was not currently fashionable in donor circles. Others concurred, raising the age-old development spectre: how local knowledge and expertise - about what works in particular contexts - is repeatedly overridden by Northern agendas, even to the detriment of success.

During my teams’ time in the Philippines, we heard some inspiring examples of environmental activists making creative use of digital technology. But these organisations were not accessing innovation funding. It made me wonder whether development innovation funders should be thinking differently about how to find and support new ideas and approaches.

The challenges of existing development innovation funding

Let me explain my thinking. Many development innovation funders currently use approaches to stimulate new technology applications that have emerged from other sectors such as the military and business. These include challenge funds like X Prize and Development Innovation Ventures, and the ever popular hackathons. These processes encourage organisations to put tried-but-perhaps-not-trusted methods to one side and chase money available for “innovation”.

Innovation funds are located far away from grantees

Currently innovation for development funds are headquartered in London, Washington, New York, and San Francisco, far away from the places where they are seeking to encourage innovation. These funds put out calls for proposals that are responded to by organisations working thousands of miles away and then make their funding decisions based mainly on formal paperwork (e.g. the proposal, reports, etc.). Visits to meet innovators or understand their operating contexts are rare. This is for a variety of reasons, including the incentives and culture of the development sector as a whole. But one of the unintended outcomes is that development innovation funds overlook local knowledge and overemphasise ‘innovation’ as an end itself. Of course, in all the required paperwork, there will be questions about how the novel use of technology will fit the context and how it will fit into, work around, or overcome current power-relations. But because answers are not verified, there is an incentive for applicants to downplay the complexity of the contexts in which the innovation will be implemented. This is especially critical in areas such as transparency and accountability (the focus of our workshop in Manila) where context is queen.

Short grant time-frames

To make matters worse, grant windows tend to be far too short, typically last between 6 and 24 months. This is barely enough time for an organisation to gain an understanding of how the introduction of technology will affect their work and the people they are working with. Who will the technology help without further intervention? Who will be excluded by the technology? Whose capacities will need to be built and how? What offline or non-technological measures will be needed to ensure that the technology or innovation is leveraged and that those excluded are not adversely affected? How do you ensure powerful leaders do not seek to sabotage your project? How do you get buy-in from all necessary stakeholders? How do you build awareness? These and many other questions may seem to be superfluous at the design stage of an innovation project, but they come to have a major impact on the process once the project is in motion. Working out the answers is often a painstakingly slow and iterative process that can take longer than the duration of a challenge grant. One of the results of the growth of innovation funding is that funding is relatively small-scale and available for short time-frames, leading to a growth in what has memorably been called ’pilotitis’.

Inaccessible grant application processes

By their very nature applying for these grants is also exclusive. It requires the dedication of time and money to engage in a process where the likelihood of securing funding is low. For example the first Gates Grand Challenge on health in 2003 had over 1500 applications with just 43 grantees. Many of the entrants spent thousands of dollars on building prototypes and developing their ideas. This can be a barrier to entry for actors in developing countries, placing further limitations on contextually grounded applications. Grant application processes can also be exclusive: organisations must write proposals in ways that sell the organisation and their idea, and this requires having someone on the team that is aware of what the current fad being funded is and how to ‘talk the talk’ that donors want to hear. Relying on such processes can and does disincentivise innovative but resource-poor organisations from applying.

Funds overemphasise technology and overlook necessary analogue approaches

Moreover, many innovation funding schemes have been emerging at a time where organisations working on transparency and accountability find it increasingly difficult to secure funding for the existing programmatic approaches and methods they have used in the past. Although technology and innovation are sexy topics for donors and grants are available for organisations seeking to implement them, the same cannot be said for traditional analogue methods for enhancing citizenship and voice. Funding is less easy to come by to organise citizens, engage them in participatory processes, or to bring citizens, political officials, and civil society in the same room to speak to each other. It is even less easy to come by for organisational purposes such as paying salaries, covering transport and logistical costs, and buying supplies. Consequently some initiatives that would not otherwise use technology apply for tech4dev grants just to get enough funding to stay afloat rather than actually wanting to use technology. In addition, because technology is seldom ever a solution on its own, tech4dev initiatives that would almost always benefit from having the funding to do the vital analogue tasks are only able to do them to a limited extent because of the demand that technology remains the centrepiece of the programme and any deviation of funds from piloting the technology to doing something else would be frowned upon by donors. As a result, the analogue foundations of digital development, highlighted as vital by the World Bank WDR in 2016, become sadly neglected.

In sum: innovation funds are generally located far away from, and don’t have resources to visit grantees. They push innovation in short time-frames without giving adequate attention to contextual and local knowledge. The funds provided by them are most accessible to those with the resources, knowledge, and capacities to engage in dominant innovation discourse. And the funds overemphasise technology while disregarding complementary and often necessary analogue investments. It is then no surprise that the pilots that are funded by these innovation funds almost always fail to spark successful innovation.

While these problems are widespread, they are not inevitable or unavoidable. What I saw whilst examining Making All Voices Count-funded projects in the Philippines suggests that a complementary approach could more closely match the self-determined needs and priorities, of local actors and deliver better return on investments. I call it innovation scouting.

How innovation scouting might overcome these issues

Innovation scouting would involve donors sending or stationing scouts to locate talent and existing processes requiring scaling. This would ensure that scouts are immersed in the environment helping them to see the world from the perspectives of those that innovations are intended to reach. Given their continuous engagement with the place they live in, scouts (ideally people from these places rather than from abroad) would pick up on not only those things that are captured in donor reporting mechanisms, but also tacit knowledge about how things work along with the peculiarities of the place they are working in and how to navigate them.

Like with sports, these innovation scouts would be well connected with diverse sets of people in the areas they work in and would rely on local knowledge to find the top players, scouts for tech4dev projects would get involved in community forums, engage in civil society assemblies, attend local makerspace events and hackathons, etc. This is the type of seeking strategy that allows sports teams to find star athletes growing up in poverty despite not having the amenities some of the better off athletes in easier to reach places may have. If sports teams were to rely on calls for proposals and challenges to find talent, only those athletes able to read and write and with access to a device with a decent resolution camera and the means to send that video would ever be considered. Similarly, scouting would allow already successful and potentially successful tech4dev initiatives operating in the shadows to be uncovered. Time, money, and proposal writing capacity would no longer be an obstacle.

Just like athletes do not become stars or even ready for professional competition overnight or during the course of 6 months to a year, there is no reason to believe that the act of writing a successful proposal will translate in an organisation being able to innovate. Innovation talent development would be a slow process. The innovation scout would have to spend time with the organisation carefully analysing its strengths, weaknesses, needs and its likelihood to be successful. If the scout deems the organisation likely to succeed he or she can then go ahead and make investments that build on the organisations strengths, overcome its weaknesses and fill its needs. Unlike tech4dev funding today which ties organisations down by predetermining what can be done with the funding - mostly technical and technology related aspects - scouts would also assess and at times decide to fund the mundane things nobody seems to want to fund but often make or break tech4dev projects: analogue activities (e.g. bringing people together face to face), salaries, contextual analyses, finding and hiring appropriate talent, employee training in areas such as financial management, awareness building, travel and logistical costs.

One of the organisations that we met in the Philippines is a great example of an organisation not currently funded by challenge funds that a scout might find. PNNI has developed a community-based approach to holding environmental criminals to account by using existing technology appropriately to complement their analogue work. And they refuse to chase donor fashions in ways that would deflect them from their core competence. Their core approach is training communities in their legal rights and ways to protect their communal land from illegal logging, mining and fishing. They use mobile phones with built in GPS to take photographic evidence of illegal activity which is geo-tagged, time-stamped and logged using GIS software and is thus admissible as evidence in a court of law enabling the community to effectively hold environmental criminals to account.

However, the organisation does not necessarily look at its work as tech4dev work and does not think of their use of technology as being central to their work. Helping and training indigenous communities to hold illegal loggers, miners, and fishers to account is. Technology was (as it should be) just seen as a means to doing what is important. In the process of doing what is important, an innovative use of technology has arisen organically through a combination possibly never used before [an innovation!]: pictures + geotagging = evidence that can be used at a court of law to hold environmental criminals to account. PNNI’s director emphasised that they have already figured out the use of technology in achieving their goals. He mentioned that his organisation would likely refuse any funding to implement technology, especially if a donor may require PNNI to take a new technological approach or use a newer, sexier technology such as a drone. Instead, he emphasised their compelling need was funding for the mundane activities that nobody wants to fund such as organising communities and raising their awareness about their environmental right, hiring more staff, paying their salaries, and covering logistical costs including fuel and food for staff making trips to communities. This would allow the organisation to do more of what they already do well: hold environmental criminals to account.

Calls for proposals and challenges did not and probably would have never captured such an appropriation and innovative use of technology at the grassroots level. Given that PNNI does not receive tech4dev funding and their use of technology is not well-reported, we had never heard of the organisation until we met them at a roundtable that a Making All Voices Count grantee had helped us organise with organisations involved in environmental activism and communities affected by mining in Palawan. We arrived at the roundtable with the presumption that we would likely not find any use of technology but instead we left blown away by the most innovative and appropriate use of technology we came across during our trip, despite interviewing others who did receive tech4dev funding. Although PNNI’s success may not be formally evaluated yet, their headquarters provides a remarkable narrative documentation of successes. It also acts as an environmental museum housing hundreds of chainsaws, explosives, weapons, boats, and other tools confiscated from the environmental criminals they have held to account.

Tree made of chainsaws at PNNI confiscated from environmental criminals

Similar to how we learned about PNNI’s innovative use of technology through a roundtable discussion, a scout may get people together in similar ways to uncover innovative uses of technology or innovative practices more generally. There would definitely be some challenges to implementing such a funding mechanism. Most obviously, the sports analogy does not fit tech4dev perfectly. The difference here would be that after protecting an athlete, sport scouts do not necessarily have to worry about the external environment deteriorating their investments especially if they could move the athlete to a more suitable context with better training facilities. This is not possible with tech4dev initiatives. These initiatives will forever be grounded in their environments and this will shape what the initiative can do and its ability to succeed. However, scouts may also be well positioned to pull the switch or put funding on hold or reorient it to other activities when it becomes apparent that the political, economic or social environment will impede the initiative from making progress.

There are of course many potential issues that would have to be worked before innovation scouting could be implemented in the development sector, which I will leave for a future post. And some initaitives have already been experimenting with such approaches – not least Making All Voices Count, which incorporates scouting-style approaches into their country engagement work. There are no doubt useful lessons to tap into from these and other similar efforts already underway (and please do share any examples and lessons in comments below if you have them).

My experience speaking to actors involved in organisations working in the tech4dev field beyond the Philippines has convinced me that we will have to find ways to overcome the issues and build on lessons, so as to bring about a step-change in current tech4dev funding mechanisms. The silence in the room in Manila spoke volumes about how Northern donor agendas distort good development practice. Scaling existing successes through scouting may provide better return on donor investments, and be a more empowering approach to innovation and development as a whole. In light of the above, perhaps scouting is an idea that would be worthy of some innovation funding?