This blog reflects on key lessons for designing projects.

For innovation to make sense it must represent what is plausible and meaningful to the users. In October 2014, Making All Voices Count and Diocese of Kitui – Catholic Justice and Peace Commission launched project, Enhancing the participation of women in devolved governance in Kitui County, targeting women and women leaders in Kitui West and Mwingi West constituencies.

The project’s focus is twofold; Social accountability through engaging women in the budget-making and tracking processes at the county level, and monitoring of development activities funded through county budgets to ensure prioritisation of women’s issues and needs.

Why is the focus on amplifying the voices of the women within this particular context?

There is still inequality and oppression of women and women’s rights. Women in Kitui and Mwingi West sub-counties are marginalised, not necessarily in numbers – the county governor in the region is a woman – but marginalised in the sense that avenues of dialogue between women and the county leadership are non-existent.

Having women represented at the top of the leadership pyramid does not necessarily mean that the needs of the women are incorporated into development issues at the local or national level.

Women in Kitui County participate in devolved governance using technology in their own language, Kamba

What innovative tools are most plausible in meeting the demands of grassroots projects such as this one?

Kitui County has relatively poor infrastructure to support high-tech innovation. Electricity access is 4.8%, good roads 39.9%, paved roads 2.4% and the poverty rate is estimated to sit at 63.7%. The local people are mostly of Akamba constituency and therefore the use of English and Kiswahili has proved a huge challenge in getting the participation of women in matters of devolution.

How has the social and cultural context influenced project activities?

The project was designed to send out SMS alerts in English and Kiswahili and to obtain feedback through the same channel on budget-making processes and service delivery at the county level. However, on attending one of the community forums, the entire session was held in the local language, Kamba. Reactions, comments and feedback to any of the issues raised were in the local language.

On further testing, the first two SMS were sent in English, but the recipients never responded, calling for a change in strategy and more specifically the language used.

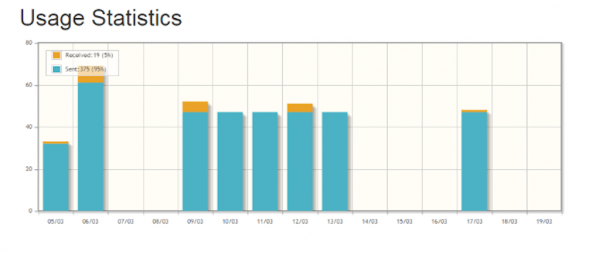

The graph below shows an increase in SMS responses after moving from English to the local language.

Though response is still minimal, there has been a noticeable increase in responses when the local language is used. The messages are received in the local language, translated into English and analysed for future activities to inform subsequent SMS responses.

This reiterates the value of pre-testing and baseline surveys to understand the social and cultural context in which technology and innovation projects should be built on.

The project is incorporating other tools, such as the use of traditional songs recorded and aired on radio which will provide an innovative avenue not only to engage, but to retain those who are marginalised through the extensibility of the project: supporting use of local language and wider geographical coverage.

Key lessons learned:

Creating a sense of local ownership is key. Through the use of SMS in the local language, recipients felt empowered to communicate and could clearly articulate issues.

Working with the existing infrastructure, and building innovation based on local resources is critical in overcoming barriers such as limited electricity and internet connectivity.