Over the last 12 months, WaterAid, Itad and IRC Wash have conducted desk-based research to understand the reasons why some ICT initiatives to improve water supply in rural areas may succeed where others don’t.

The team have produced a series of blogs reflecting on the research and, in this post, we introduce some of the key research questions and a first look at our findings.

The challenge of improving water supply schemes

In rural sub-Saharan Africa, it’s estimated that up to a third of all water supply schemes fail within five years of becoming operational. But this is an estimate – it’s difficult to actually find any data on how well rural water supplies are functioning, and the data available is often unreliable and not up to date.

This lack of solid information causes major problems with tracking how well water supply schemes are functioning and making sure necessary repairs are carried out. Ordinary people who actually collect water, particularly women and children in rural areas, are often left outside of conversations on how to manage water points and have no way of reporting breakdowns and getting support to fix them.

What's our research about?

Unfortunately, not many ICT initiatives have been well-documented, except on an operational level. With the exception of the excellent blogs about the Maji Matone initiatives in Tanzania, there has been very little reporting on whether these initiatives have actually succeeded in improving water supply functionality and what the reasons for success or failure were.

That’s why we decided to look in more detail at some of the recent ICT initiatives that have been introduced and try to identify the key factors, either in how an initiative is designed or in the context it is being introduced, which have a real impact on whether an initiative succeeds or fails.

How have we designed our research?

We used a literature review and an online survey to identify eight ICT initiatives that aim to improve water supply functionality, predominantly in rural areas:

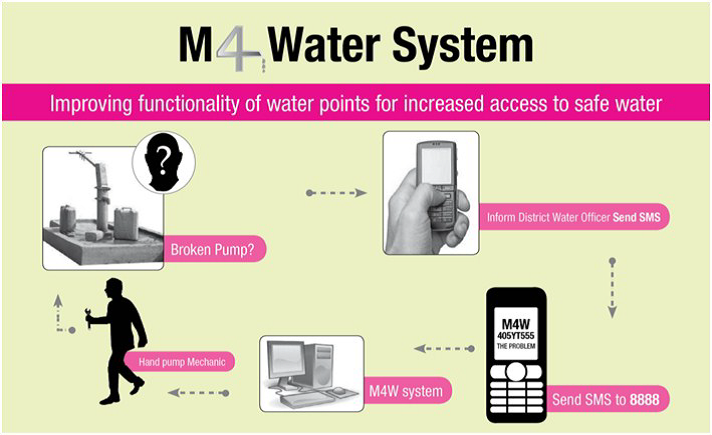

- Mobile Phones for Water (M4W) in rural districts of Uganda

- Maji Voice in the cities of Nairobi and Nakuru in Kenya

- Maji Matone in rural Tanzania

- Next Drop in the cities of Bangalore, Hubli-Dharwad and Mysore in India

- SIBS in rural Timor Leste

- Re-imagining Reporting in rural Bolivia

- Human Sensor Web in Zanzibar Town

- Smart Handpumps in rural Kenya

We defined success of these initiatives by three main outcomes:

1) Functionality of the ICT mechanism

2) Processing of ICT reports by governments or service providers

3) Improvements as a result of the reports

We also carried out interviews with people who had designed and worked on these initiatives and who, through their experiences on the ground learnt a great deal more about the design of these initiatives and the contexts in which they were introduced.

Finally, a research method called Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) was used to compare the different initiatives and to identify certain factors that were always, or tended to be present when an initiative was successful in achieving the three outcomes set out above.

What did we find out?

Our findings will be explored in detail in the next blog on 13th August, but it is worthwhile pointing out how many of these key lessons can be distilled into some pretty obvious phrases.

Lesson 1: Don’t re-invent the wheel

People are much more likely to report on how well water supplies are functioning if the ICT mechanism for making the report – whether sending an SMS, making a phone call or using the internet – is already something they are comfortable using. For example, in the case of Mobile Phones for Water (M4W) in Uganda, people preferred to make a missed call to a known person rather than sending a text to an unknown number, making them less likely to use the M4W initiative to report breakdowns. This detail matters.

Lesson 2: Find out what’s possible

Successful projects have done their research to find out what is – and is not – possible for their target groups. If project teams want people to report via SMS, they are checking whether the reliability of mobile phone reception, availability of mobile phone charging facilities and whether those making the report can actually afford the cost of reporting it.

Lesson 3: Be realistic about what you can expect from people

A more unexpected result of the research was that ICT initiatives were more likely to be successful if the actual reporting was carried out by government or service-provider staff, rather than carried out by community crowd-sourcing when a breakdown takes place.

This could highlight the continued problems in empowering water fetchers themselves to directly report failures, although arguably the initiatives led by governments and service providers can still strengthen the voices of water users by giving users the opportunity to feedback. Whether they actually do this will depend on the design of the specific initiative but will be something that needs to be considered by future initiatives, particularly given the target in the United Nations’ (UN) recommended Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to strengthen community participation.

Lesson 4: Money almost always matters

We also found out that the processing of ICT reports is more likely to be successful if the related operational costs are met by a government body or service provider and not by a third agency such as an INGO. It is also likely that this will ensure better long-term sustainability initiatives, as the government or service provider will often feel ownership (and indeed local pressure to perform) – because of their funding cycles, an INGO will only support a project for a limited length of time.

Similarly, successful projects are careful about who they partner with – mainly institutions that can afford internet connectivity and pay for (and retain) good staff who actually have knowledge about processing ICT reports about water point functionality.

Finally, less surprisingly, we found that water point repairs are more likely to take place, based on ICT reports, when:

- There are sufficient funds to pay for the repairs

- Spare parts and mechanics are available

- The responsibilities for operation and maintenance are clear to all parties.

In the cases of Smart Handpumps, Maji Voice and Next Drop, maintenance was carried out by the same party that received and processed the ICT reports. These three initiatives achieved all defined outcomes of success: (1) successful ICT-based reporting; (2) successful processing of ICT reports by governments or service providers, and (3) successful water service improvements.

About the author

Jen Williams is an international development consultantAbout this blog

WaterAid, Itad and IRC will publish the full research report on the Making All Voices Count website soon. On 8 September, IRC will host a webinar to discuss the research results in depth. Email Joseph Pearce (pearce@ircwash.org ) if you are interested in joining the webinar.Related content

-

BLOG | October 12, 2015

Responsibility leads to responsiveness: Lessons on using ICTs to improve… -

BLOG | August 6, 2015

Testing the waters: How ICT reporting improves rural water supplies -

BLOG | August 18, 2015

How do ICTs improve access to water services? -

BLOG | September 30, 2015

What we're learning about using ICTs to improve rural water… -

PROJECT | August 13, 2015

Lessons from ICT projects to improve rural water supplies -

PUBLICATION | April 28, 2016

How can ICT initiatives improve rural water supply? -

PUBLICATION | July 16, 2015

Testing the waters: a qualitative comparative analysis of the factors… -

PUBLICATION | January 31, 2016

ICTs help citizens voice concerns over water – or do…