It’s enough to make even the most experienced of facilitators nervous: the first morning of a three-day learning event, facing a group of sixty people from eighteen countries, half of whom are a very diverse set of brand-new grantees starting up tech-for-transparency-and-accountability (Tech4T&A) projects, and the other half of whom are seasoned, well-known, expert practitioners, analysts and thinkers in the field. How to satisfy such a wide-ranging set of learning interests? Could we even assume that they were all interested in learning? Perhaps most of them were only there because their presence was required by their new funder, Making All Voices Count?

Until I see feedback from the independent evaluation conducted at the end, I can’t know how far the Making All Voices Count Learning and Inspiration Festival, held in Tanzania last week, did satisfy that wide range of learning interests. But I do know that, at least by the time they left, the participants were interested.

We sought to achieve two things with the event. Firstly, to help bridge the very different life-worlds of key groups of actors who collaborate – or try to collaborate, or are assumed to collaborate – in T&A and Tech-for-T&A projects: principally, techies, development people, government officials, social activists and private sector actors. Secondly, to help turn evidence into practice and help ensure that practice within Making All Voices Count would generate evidence, to meet a variety of needs at several levels of T&A practice and theory.

Dynamic thematic learning sessions on Day 1 tapped and shared participants’ experience and deepened our evidence-based knowledge on four thematic areas. The feedback at the end of a long and full first day reflected vibrant debates. Certain comments stuck in my mind, no doubt because they were music to my ears:

- From the session on ‘Making: Making the Tech get to the T&A’, “We talked about ‘data+’ being what leads to change. It’s the word plus that is strategic. You can’t produce change using technology.”

- From the session on ‘All: Inclusivity and Exclusion in Tech-for-T&A’, questions were posed about the role of intermediaries in mediating, acting as gatekeepers, shaping or changing the message. What is their power and influence? Do they, in fact, act as connectors between citizens and their governments? Do they help ensure that all needs and demands are equally addressed?

- From the session on ‘Voices: Representation, mediation and listening’ emerged a vision of voice as a conversation in society about developing common understandings, authoritative perspectives, but also a struggle between different perspectives within society – an interplay of voices. The need was noted for ‘tactical targeting and framing: for knowing where to direct the voices’. The session reaffirmed the words of Jonathan Fox in his 2007 book Accountability Politics, ‘If voice is about the capacity for self-representation and self-expression, then power is about who listens’.

- From the session on ‘Count: Government responsiveness – what, how and why’ came the unpacking of government responsiveness as a spectrum, ranging from repressive reactions at one extreme, to ignoring the request for policy change, through more positive reactions which take demands into account but do not respond fully, to full responsiveness at the other extreme. From here too came the suggestion that politics should not be treated as part of context, but is one of the big forces that is making a difference to whether citizens’ voices count – part of the set of enormous forces in society which are pushing government one way and the other.

(One word stuck in my mind because it was not music to my ears: the generic ‘he’ which was used widely and repeatedly when talking about innovators, tech developers, government officials and policy-makers. This stopped when the exclusionary effects of this terminology, and its incoherence in this space which was about making all voices count, were pointed out. By a woman.)

On Day 2 we had a tiny taste of Tanzania. One-day site visits are so full of obvious limitations that I’d wondered whether it was worth including them in the programme. Three things made the one-day site visits worthwhile:

- The reflections afterwards, on how those very limitations had shaped participants’ behaviour and experience of the visits. Participants noticed that they had gone into the usual default mode when visiting poor and marginalized people. They had counted the lacks and the needs – the clinic beds; the numbers of classrooms, teachers and pupils; the deficits in hygiene at the health posts. They then noticed that they had counted those because they could see them, and had been unable to see the things that were the focus of the learning event – unmet citizen demands, governance relationships or lack of them (we only heard about tax collection, no other relationship with government), the existence or quality of feedback loops about service provision, any but the most obvious signs of social diversity between different groups of citizens. This was a site visit especially designed to explore these issues, by a group of individuals with a particular interest in exploring them, and yet these aspects of ordinary Tanzanians’ lives had eluded observation. What can be learnt from this by the tech innovators, the database scalers, the app designers, whose design phase often doesn’t include any fieldwork or reality check at all?

- The realisation that my general scepticism about poor and marginalised people’s access to tech for T&A partly reflects the rural bias in my own experience – but only partly. The urban Tanzanians we saw and met in Dar es Salaam, men and women alike, certainly had mobiles, opportunities to charge them, and money to buy airtime. Asked what they used them for, though, people reported using them for income generation and social and family purposes. No-one, even in this densely populated area in the capital city with full mobile network coverage, saw them as a means for voicing citizen demands to government or providing feedback to service providers.

- The tension between individualist technologies and general accountability problems which require collective solutions. It has long since been recognised that one of the few advantages marginalised people can count on in the struggle to survive injustices and deprivations is their numbers and, with that, their scope for collective action to realise their rights and hold the governments and other powerful actors to account. It has since been acknowledged that this potential is thwarted by ‘collective action problems’- the costs of organizing and working together, which can be prohibitive for poor, isolated, marginalised people. On the other hand, in this corner of urban Africa the internet seemed as obsolete as the typewriter in European capitals: connectivity was clearly via smart-phone. Most mobile-based transparency and accountability initiatives I know of work – well, purport to work – by reducing the cost to individuals of taking action for accountability, requiring them only to send an SMS to a short-code number. Mobile-based Tech-for T&A, far from facilitating collective action, offers individuals a way to bypass the need for collective action. But how can individual actions, however many they turn out to be, ever overcome chronic, engrained problems of unaccountable governors and undemocratic governance dynamics?

And here I was, musing about accountability, in a muddy street of this poor neighbourhood of Dar es Salaam, surrounded by stagnant puddles nurturing mosquito eggs, beside a footbridge which is an essential route in and out of the community, was initially installed thanks to private philanthropy, collapsed in floods two years ago, and has remained broken for two years despite the local Chairman’s ceaseless efforts to get the municipality to fix it. . My musings took me back to the World Development Report 2004’s 'short route of accountability.'

But just at the point when this recanting over the short route began to restore the notion of accountability as politics, along came the short-code route of accountability: get your phone, text this free number, and hey presto!

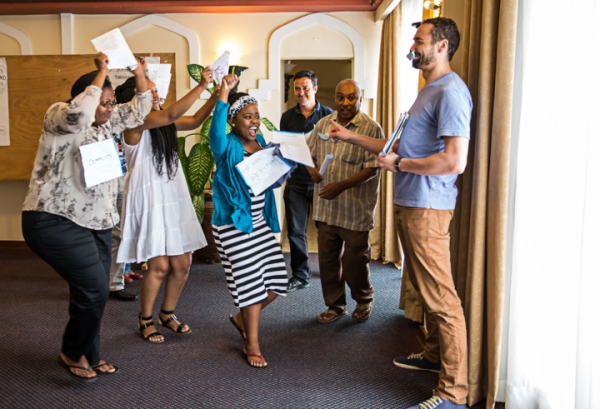

Late on Day 3 of our learning and inspiration event, as we pieced together what we had got from the event in the way of bridging life-worlds and turning evidence into practice, it was gratifying to hear participants saying things like “Already we are forming partnerships for working as we move forward”, and “I can now see that there are two tensions we have to think about: tactical Vs strategic; and technical Vs political”.

But a more significant achievement was that, as a programme known for its promotion of technology for T&A, we had managed to voice a warning: “Beware of the short-code route of accountability. That route leads only to decent customer service, not to accountable governance”.

And we had been listened to.